Native Americans and the Revolutionary War

The eighteenth century was a troubling time for the native people of North America. Gradually, the population of foreigners grew. Initially, they coexisted in peace. The Natives gave valuable support to their new neighbors, who could not survive otherwise. Eventually the Europeans desired to occupy more and more of the rich wilderness of the unmolested continent. Before long, the Natives found themselves in the way of imperialist powers set on carving up and claiming the whole world. Life would never be the same.

The French and Indian War

Long-time enemies France and Great Britain were setting up camp in North America. On the east coast, the British were harvesting the abundance of the sea and flexing their naval might. Inland, the French were getting rich on the fur trade. Both nations wished to expand west.

The French were aware of their need to work together with the Natives to learn the weather, wildlife and geography. Also intermarriage between French trappers and Native women built family bonds. So when the British and French erupted into war, many of the Native tribes sided with the French, who were heavily outnumbered and needed the support.

The war lasted from 1754-63. The French were unable to defeat the waves of British troops supported by the world’s strongest navy. At the end of the war, Great Britain signed the proclamation of 1763, forbidding colonists from settling west of the Appalachian Mountains. In theory, this protected the lands of the Natives. In fact, it enraged the colonists who felt westward expansion was something they had fought for and won. The Natives were a conquered people and their territory should be surrendered.

The Reactions of Individual Tribes

Native Americans are composed of multiple tribes across the continent, each culturally distinct. Each made its own decision on how to navigate the political world of eighteenth century North America. Alliances were built and broken.

Algonquin – Native to New England. Allied with France during the French and Indian War but with Britain during the Revolutionary War.

Abenaki – Native to New England and Quebec. Forced north because of British settlement. Allied with France.

Shawnee – Native to Ohio and Kentucky. Allied with France until signing the Treaty of Easton in 1758, in which several tribes allied with Britain in exchange for settlements and hunting ground in the Ohio Valley.

Lenape – Native to the Delaware and Hudson rivers. Forced toward the Ohio River by European settlement and Iroquois expansion. Allied with the French but attempted diplomacy with the British. Allied with the Colonists during the Revolutionary War.

Micmac – Native to northeastern New England and the Maritime provinces. Fought British settlers before the French and Indian War. Allied with the Abenaki tribe but stayed out of the wars. Later settled in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland.

Ojibwa – Native to the Great Lakes area. Enemies of the Iroquois nation. Allied with France during the French and Indian War and with Britain during the Revolutionary War.

Ottawa – Native to Lake Huron, Michigan and Ontario. Allied with France during the French and Indian War and with Britain during the Revolutionary War.

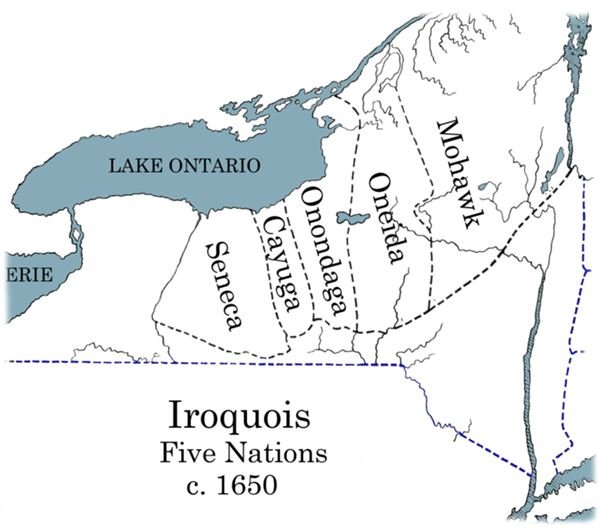

Iroquois – Native to New York State. A confederacy of six nations: Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca and Tuscarora. Disagreed about how to approach the French and Indian War, with most staying out. Split regarding the Revolutionary War. Joseph Brant led the Mohawks, Cayugas, Onondagas and Senecas against the British while the Oneidas and Tuscaroras joined the Colonists.

Catawba – Native to the Carolinas. Allied with the British during the French and Indian War but with the Colonists during the Revolutionary War.

Cherokee - Native to the Carolinas, Georgia and Tennessee. Allied with the British during the French and Indian War, but the alliance deteriorated into the separate Anglo-Cherokee War in 1760. When colonists failed to respect the Proclamation of 1763, young Cherokee warriors, in defiance of their elders, attacked colonial settlements.

The Revolutionary War

Many tribes saw the Proclamation of 1763 as a move of peace by the British government. While the crown wished hostilities in North America to cease, colonists saw territory they won in battle given back to their opponents. Most tribes chose to stay neutral or side with the British against colonists devoted to taking over their land.

Both the British and the colonists publicly urged the Natives to remain out of their battle. The Second Continental Congress of 1775 prepared the following statement:

This is a family quarrel between us and Old England. You Indians are not concerned in it. We don’t wish you to take up the hatchet against the king’s troops. We desire you to remain at home, and not join either side, but keep the hatchet buried deep.

However, in a fierce war both sides were willing to take every advantage, including alliances with particular tribes and employment of Native scouts.

Aftermath of the Wars

The British and the Natives who fought beside them were unable to defeat the colonists. Again, the revolutionaries felt they had fought for and won the lands to the west. The Natives, as a whole, were a combatant that had fought against them and lost. They were treated as a conquered people, unilaterally.

The Peace of Paris in 1783 involved the signing of treaties between Great Britain and the victorious colonists. The victors were granted the Thirteen Colonies and all lands west to the Mississippi. The British ignored the rights of their former Native allies and gave away what was not theirs.

This began the period of westward expansion the colonists had been so hungry for. Disregarding the people who had lived their whole history there, they forced their way past the Mississippi all the way to the Pacific.

References

- Iroquois Confederacy - http://www.everyculture.com/multi/Ha-La/Iroquois-Confederacy.html#b

- Which Indian Tribes Fought in the French & Indian War? http://www.ehow.com/info_8147012_indian-fought-french-indian-war.html

- Indians and the American Revolution - http://www.americanrevolution.org/ind1.html

- Stories from the Revolution - http://www.nps.gov/revwar/about_the_revolution/american_indians.html

- Death of General Wolfe by Benjamin West, painted in 1770, image in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- By R. A. Nonenmacher (w:Image:Iroquois 5 Nation Map c1650.png) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons