Truths and Misconceptions about Harems and Women in Turkey

Purpose and Origins

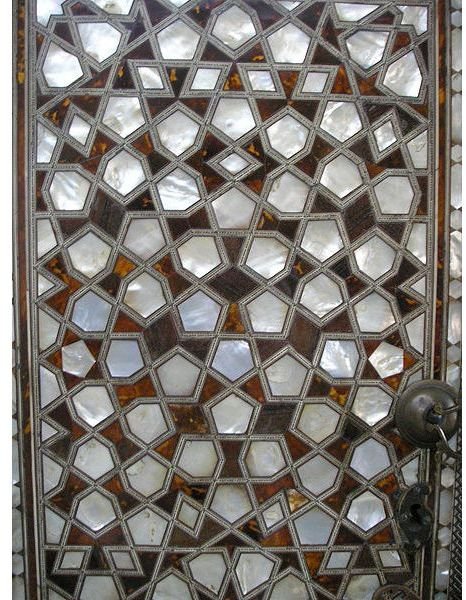

The word “harem” is of Arabic origin and refers to the forbidden quarters of a Sultan’s household where women lived. The most famous of all these exclusive women’s quarters was the Topkapi Saray in Istanbul, home to the Ottoman rulers and their families. It was a palace within the palace, housing hundreds — even thousands — of wives, concubines, children, eunuchs and chambermaid slaves. But it was not only a living quarters, or the slave pen of beautiful harem women it is typically thought of by Westerners. It also contained a hospital, schools and a separate mosque serving the women.

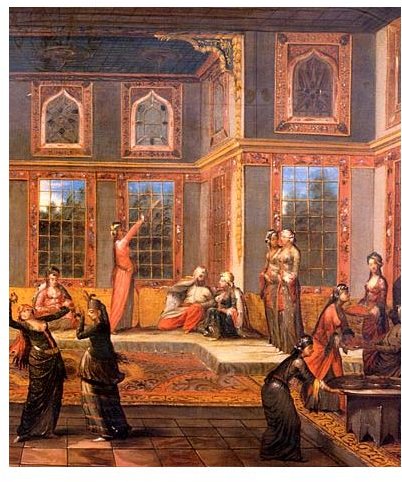

Education of the women within its walls was one of the foremost priorities of harem management. They were not there solely to look pretty and provide for the Sultan’s pleasure, but were also taught religion, mathematics, embroidery, singing, music and literature. The goal of this education, similar to that of upper-class European women, was to prepare them for lives as suitable, cultured wives to elite government officials and princes.

Heirarchy

This women’s society within a society was ruled by a rigid hierarchy based on laws of strict obedience. Those who disobeyed were severely punished, including a death penalty by drowning. At the top of this heirarchy was, not a man, but a woman — the ruling Sultan’s mother. She went by the title of the Valide and also held the title of Queen. Her power came from her son the ruler, but she was also a formidable political figure in her own right. The women at the lowest rank came under her rule as slaves — captured as prizes during conquests of other countries and sold into captivity. Once there, these captives did have a chance to better their fate and advance through the ranks by improving their education, beauty and skills. Through a graduation system, girls who qualified were presented to the Sultan. If they pleased him, they might advance to the status of concubines. If they became pregnant, they became wives. There was no discrimination against legitimate versus illegitimate heirs as in European society — all sons were equal contenders to the throne.That in itself was a hotbed for power struggles, both amongst the sons and amongst their mothers.

As a whole, the Western impression of life behind the purdah is one of laziness, luxury, sex and imprisoned women. The romanticism surrounding the image of this mysterious feminine domicile comes from travelers of Victorian times who were never allowed access to an actual living quarters, and therefore let their imagination, fantasy and cultural values and judgments paint a romantic picture of the women’s slave pen in literature, travel journals and art.

Hürrem

Because of their unique placement in palace life, the wives of powerful sultans and politicians were often well-placed to rule behind the scenes. While history notes their husbands and sons as princes, conquerers and kings, the efforts of these women are often forgotten or simply unknown. Three women in particular, Hürrem, Nurbanu and Kosem, played instrumental political roles in securing the throne for their sons and supporting their husbands behind the scenes.

Hürrem was the wife of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, who came to power in 1520. She entered the women’s confines as a slave girl taken from the Ukraine, but her extraordinary beauty and intelligence helped her rise quickly through the ranks. She received the finest education available for a woman and managed to capture Suleiman’s eye. He was the first sultan to marry a concubine. Hürrem “cast her spell” over her husband and soon became indispensable to him — romantically and politically. In his absence, during his many wars and conquests, she essentially ruled in his place. She proved a cunning ruler who did not shy away from intrigue or even murder to ensure the safety of the throne and the succession of her son. She died before Suleiman, and he never took another wife — either during her lifetime or after her death.

Nurbanu

Nurbanu was the wife of Hürrem’s son Selim, who followed his father to the throne. She was originally a Greek slave, but like her mother-in-law, came to great influence through intrigue, conspiracy and cold malice. She had a political mind and negotiated with the Venetians, commissioned famous architects, built mosques, hospitals and inns and — again like her mother-in-law, Hürrem — resorted to murder if it suited her plans.

Kosem

Kosem was the wife of Ahmed I, who came to power in 1603. After the short reign and premature death of her older son, Murad, her younger son, Ibrahim the Mad, succeeded to the throne. As his name suggests, he was not a very good ruler. By that time, the once powerful Ottoman Empire was in chaos, and the Sultan could do nothing to prevent the threat of rebellion and dissolution. Kosem decided to take matters into her own hands. Rather than let the empire fall into chaos, she killed her own son. Kosem’s grandson inherited the throne, but she did not forsee the unexpected power struggle with his mother, Turhan. Accustomed to ruling her sons behind the scenes for 30 years, Kosem probably underestimated her rival. Finally, the tables turned on her; Turhan’s own followers hunted Kosem down. An eunuch strangled her with a curtain in a cupboard.

Harem life, as well as the lives of harem women, was much more colorful, exciting, intriguing and militant than the Victorian travelers could imagine.

References

- Peirce, Leslie P. “The imperial harem: women and sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire” Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Source: author’s own experience.

- Harem scene with the Sultan by Jean-Baptiste van Mour under Public Domain on Wikipedia Commons; Valide Sultan Dairesi Harem, Topkapi by “Gryffindor” under Public Domain on Wikipedia Commons; Kosem Sultan, author unknown, under Public Domain (PD-US) on Wikipedia Commons.